IFCDC- Recommendations for Best Practices for Feeding, Eating and Nutrition Delivery

“Imagine…against all odds, and all the setbacks, you are able to hold and breastfeed…your little one grows…and after almost four months in the hospital, that little tiny human who struggled so hard, may get to go home…soon.”*

These committee members had primary responsibility for this section:

Erin Ross, PhD, CCC-SLP

Joan C. Arvedson, PhD, CCC-SLP, BCS-S, ASHA Honors & Fellow

Jacqueline McGrath, PhD, RN, FANP, FAAN

White Paper | First Fragile Infant Forum for Integration of Standards: Feeding, Eating, and Nutrition Delivery (download)

Executive Summary of the White Paper

Questions to consider when starting your process Management Of Feeding Eating And Nutrition Delivery

Check sheet to assess this area before and after intervention.

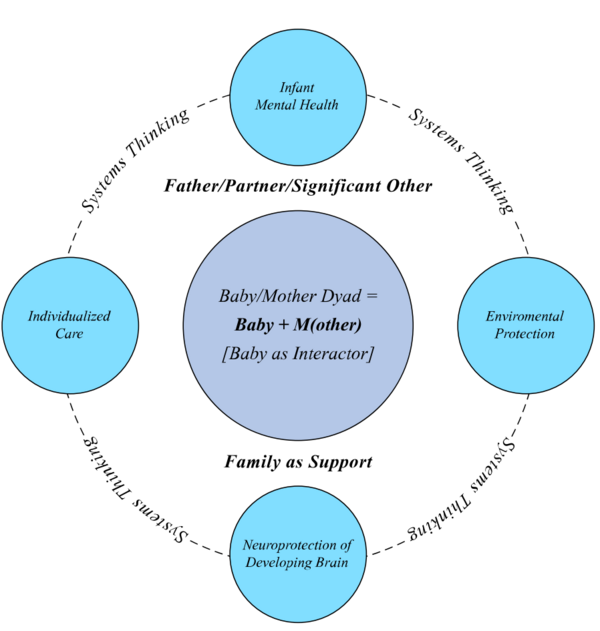

Successful change only happens in relation to the system. To review systems concepts check this section.

Standard 1, Feeding: Feeding experiences in the intensive care unit (ICU) shall be behavior-based and baby-led. Baby-led principles are similar whether applied to enteral, breast, or bottle feeding experience.

Competency 1.1: All staff shall be educated on the physiologic parameters and baby behaviors that are indicative of readiness, engagement, and disengagement. (i.e., the need to alter or stop a feeding)

Competency 1.2: All professional staff who feed babies or support m/others to feed their baby shall be trained in appropriate feeding skills, with verified competency in feeding.

Competency 1.3: Consistency of feeding practices among staff who feed an infant shall be promoted, monitored and verified.

Competency 1.4: Parents and other caregivers (m/others) shall be given information and guidance regarding how to interpret the communication of their newborn including baby behaviors that indicate safe and enjoyable feeding experiences (e.g., physiologic parameters as well as behaviors of feeding engagement and disengagement).

Competency 1.5: Professional caregivers shall support m/others to engage in appropriate responses to their baby’s communication during feedings.

Competency 1.6: All oral experiences should be based upon the baby’s behaviors and focused on enjoyable non-stressful interactions. Biologically expected experiences (tactile and feeding) shall be the primary focus rather than exercise/therapy driven interventions that are not part of a healthy fetus or newborn’s experience. Non-critical care oral experiences that cause distress or instability (e.g., changes in heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), saturations, color changes, crying, hiccupping, yawning, gasping) should be minimized.

Competency 1.7: Baby behavior at the beginning (baseline) of feeding as well as changes during feeding for physiologic, motor, behavioral state, and interaction parameters shall guide the feeder’s decision to continue or discontinue the feeding. While some loss of stability is common, the focus shall be on maintaining a minimal level of baseline physiologic stability and behavior throughout the feeding or regaining baseline stability when the baby loses stability during the feeding.

Competency 1.8: When professionals/caregivers determine best delivery of enteral feedings, in addition to nutritional considerations, the baby’s physiologic and behavioral responses shall be considered.

Competency 1.9: Baby behavior as well as medical stability shall guide initiation of oral feeding attempts as gestational age does not address normal variability seen in development or with the impact of medical comorbidities.

Competency 1.10: Oral feeding shall be modified or stopped when the baby no longer shows stability or engagement.

Competency 1.11: Oral feeding plans shall be individualized based on the baby’s behaviors and performance, as well as overall progress.

Competency 1.12: M/other feeding preferences shall be included and supported whenever possible during the development of feeding management plans.

Evidence-based rationale:

Education about the feeding experience is vital, and involves many factors. A primary tenet of infant and family centered developmental care (IFCDC) is the importance of recognizing and responding to the communication of the baby. (1, 2) Specific baby behaviors within the domains of autonomic control, motor, behavioral state, and attention/interaction provide information to the caregiver to guide cares. (1, 2) Caregiving that responds to these behaviors (cue-based) has resulted in improved outcomes of babies. (3-15) Feeding outcomes have also been improved with programs that focus on attending, interpreting and responding to baby behaviors. (9, 11-14, 16-18)

Infant and family centered developmental care education is the standard for professional caregivers in neonatal intensive care units. (2, 19) Feeding a preterm baby and/or a baby with medical comorbidities requires a skilled feeder – one who observes and responds to the individual needs of the baby. (20-22) These skills shall be taught and competencies verified for all professional caregivers. (2, 16, 22-24) Staff education focused on the need to monitor baby stability carefully, as well as to respond to signs of instability, to improve the co-regulation of a baby during feedings. (21, 22, 24) Education should include recognizing the physiologic stress signs as well as more obvious motor and behavioral state stress signs, because physiologic stability is challenged during feedings, and can be improved when staff and families are educated and use a collaborative approach with the baby during feedings. (16, 21, 22, 24-27)

Parents generally welcome education regarding behaviors that facilitate oral feedings. (18, 20, 28-30) Most parents need guidance and practice in learning how to feed high-risk babies. (2, 18, 20, 28, 30, 31) Baby behaviors that indicate physiologic instability are not always obvious, and m/others often need support and guidance to understand how to recognize disengagement behaviors during feedings. (20, 21, 26-28, 30) M/others frequently have questions about feedings after discharge from the hospital. (32, 33) Family education and training on infant feeding, both in the NICU and post-discharge, are standard of care and improves feeding outcomes. (2, 16, 18, 20, 34-36)

Factors that influence the acquisition of feeding skills include progression through enteral feeding stages. Therefore, responses to enteral feedings should be considered. (37-42) Babies demonstrate fewer signs of distress when fed with a slower infusion rate, and may even do best with continuous feedings up through 32 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA). (37-39) Volume tolerance should also be considered with enteral feedings, as volume can affect both comfort and growth. (37-39)

Inputs that cause pain or discomfort and result in irritability or agitation are avoided to minimize noxious effects of the ICU (see pain and stress-baby, standards). Biologically unexpected inputs (e.g., odors such as perfumes) shall be avoided, to minimize unintended effects, in keeping with principles of developmentally supportive care (see other care standards). (2, 43) Babies who receive touch protocols that are not based upon biologically expected stimulation may show distress with adverse events (apneic/bradycardic episodes or oxygen desaturations) that stop when the touch protocols are discontinued. (44-47) Sensory-based inputs (e.g., touch, smell, taste) that are provided by the m/other are familiar and can improve stability and outcomes. (see skin-to-skin standards).

Feeding experiences challenge the physiologic, motor, and behavioral state stability of babies. (21, 25-27, 48-53) Babies demonstrate behaviors indicative of feeding readiness, and when fed in response to these behaviors, show more physiologic stability and transition more quickly to full oral feedings. (10, 12-14, 16, 21, 25, 54-56) With maturation, babies demonstrate improved stability in physiologic, sensorimotor, behavioral state, and interaction competence. (1, 48, 54, 57, 58) Both stability and maturation influence the development of feeding patterns. (48, 55, 59) Feeding abilities change over time, and therefore eating is considered a neurobehavioral process. (15, 48, 58, 59) Caregivers who are trained to identify and respond appropriately to these indicators can help preterm babies and their parents become co-regulators during a feeding. (20-22, 24, 28, 48, 60) Preterm babies often show more respiratory stability during breast feeding attempts than during bottle feeding. (51, 61-64) Preterm babies often struggle to maintain stability (heart rate, respiratory rate and oxygenation) during bottle feedings. (52, 53, 65) They are able to maintain temperature when breastfeeding, and some may be able to suck, swallow, and breathe at breast without adverse events as early as 27-28 weeks gestation. (61-64, 66) Mothers are more engaged during feedings where their infant is more physiologically stable, and showing behaviors indicating a readiness to eat. (20, 67)

Standard 2, Feeding: Every m/other shall be encouraged and supported to breastfeed and/or provide human milk for her baby.

Competency 2.1: Human milk should be available to all babies in the ICU (maternal or donor).

Competency 2.2: Professional staff shall provide information to m/others regarding the importance and benefits of human milk, and the influence of human milk on medical, nutritional, and neurobehavioral outcomes.

Competency 2.3: Maternity and ICU teams shall partner to communicate the importance of and facilitate early hand expression of colostrum and early and frequent mechanical pumping of human milk.

Competency 2.4: Systems shall actively encourage mothers to provide their human milk. Support for feeding challenges both with initiation of pumping and transition to breast feeding shall be anticipated and provided.

Competency 2.5: ICU systems shall support mother/baby dyads to transition to breast feeding (where possible), in additional to providing human milk by other means.

Competency 2.6: ICU systems shall provide lactation support to m/others for the entire hospital stay, from initiation of breast pumping to successful breast feeding.

Competency 2.7: Breast feeding support for transition home shall be identified and communicated to m/others prior to discharge (where appropriate).

Competency 2.8: For babies who are both breast and bottle fed, breast feeding should be initiated first whenever possible. Breast feeding should be offered for every feeding that the mother is available, as tolerated by the baby.

Competency 2.9: Alternatives to bottle feeding shall be used until breastfeeding is well established based upon the desire of the family, in consultation with the ICU staff.

Evidence-based rationale:

Human milk imparts many benefits – health as well as psychosocial. Colostrum supports growth of the gut biome, and is full of pre- and probiotics. (68-74) Human milk is protective of infection and other negative health consequences, and is related to improved body composition as well as cognitive abilities. (23, 68, 72-78) Human milk is the optimal nutrition for most babies in the ICU. (72, 74, 79, 80) Mother’s own milk is the most suitable nutrition, but donor pasteurized human milk is the second most suitable. (72, 80, 81)

Breast feeding is generally best for babies. Most babies are more physiologically stable and regulated when breast feeding than when bottle feeding. (51, 61, 62, 64) Preterm babies who are breastfeeding are able to create intra-oral vacuum; however, milk intake is related more to time spent actively sucking. (53, 82) Strategies that improve the provision of human milk include putting the baby to breast at an early gestational age, putting babies to breast as a first feeding, and skin-to-skin care. (23, 74, 83-88) Strategies to improve breast feeding outcomes include encouraging maternal involvement, putting babies to breast early and often, verifying adequate transfer of human milk, and skin-to-skin care. (83-85, 89) Breast shields may be beneficial, but shall be used only if necessary, as they may negatively influence volume consumed at breast. (82, 90) Alternatives to bottle feeding may increase likelihood of babies being exclusively breastfed at the time of discharge. (91-93) Mothers need ongoing support after discharge to breast feed successfully. (64, 83, 90) Mothers in the hospital setting require emotional support to pump for extended periods of time. (83, 85, 94) Mothers struggle emotionally with loss of breastfeeding and have more positive emotions when successfully breastfeeding. (95) Breastfeeding positively influences later feeding behaviors of both the mother and the baby. (89, 96)

Standard 3, Feeding: Nutrition shall be optimized during the ICU period.

Competency 3.1: Growth shall be measured, monitored, and optimized both in the ICU and in the early post-discharge period. High-risk infants may require human milk to be fortified for some period of time to meet their full nutritional needs.

Competency 3.2: Staff should be trained to accurately collect weight, length, and head circumference parameters.

Evidence-based rationale:

Poor growth in the preterm baby is associated with poorer developmental outcomes. (80, 97) Nutrition in the newborn period shall be optimized to improve developmental and health outcomes. (2, 79) Feeding methodology shall consider loss of nutrients, specifically fat, calcium, and phosphorous. (98) Feedings delivered via a bolus lose a smaller percentage of nutrients than continuous feedings. (98) The comfort of the baby during enteral feedings should be considered as well. (see feeding, standard 1).

Standard 4, Feeding: Mothers shall be supported to be the primary feeders of their baby.

Competency 4.1: ICU professionals shall actively work with m/others to assist them to feel confident and competent with feeding their babies.

Competency 4.2: Where relevant/necessary, bottle feeding shall be conducted by the m/other when she/he is present rather than by ICU professionals so that m/other is supported to be the expert. M/others or their designees shall be identified as the primary provider(s) of sustenance and nurturing.

Competency 4.3: Professionals shall support the parents’ understanding of their baby’s communicative behaviors, while guiding and supporting the feeding experience.

Competency 4.4: Emotional support should be available to minimize stress on the family when babies are not eating well, and/or when the family or m/other are having difficulty with their expectations for successful breastfeeding.

Competency 4.5: Extensive support and education shall be offered to m/others who are unable to be the primary feeder during the hospital stay (prior to and after discharge), to ensure confidence and competence in feeding the baby.

Competency 4.6: M/others shall be provided education in a manner that is individualized to the m/other’s learning style and ability to understand and retain the information.

Evidence-based rationale:

Feeding a preterm infant or an infant with medical comorbidities requires specialized knowledge and skills, and m/others who lack these skills may miss out on the opportunity to co-regulate their infant. (20, 22, 28, 99) Parents evaluate their own competence as a m/other by their ability to feed their baby. (100-102) M/others are motivated to nurture their babies through feeding, and feedings provide a powerful experience that shapes the parent/child interaction. (100-104) Mothers of preterm babies generally have more clinical symptoms of acute stress and anxiety, and are often more worried about breastfeeding. (89, 95, 105) Lower birthweight (BW), higher neonatal clinical risk, and longer length of stay in the ICU are associated with difficulty breastfeeding. (95) Mothers generally feel a sense of fulfillment, pride, and satisfaction when they are able to successfully feed their baby in the ICU. (89, 106) Significant parenting stress is associated with having babies with more medical risks, as well as with mothers of multiples. (105, 107) Bedside professional caregivers have a critical role in encouraging, supporting, and coaching the m/other to become confident during feedings. (2, 22, 23, 28, 31, 84, 85, 89, 94, 108) (2, 18, 68, 100, 102) M/others often struggle with their role in feeding their high-risk infants, and need emotional support, as well as information and logistical support. (2, 28, 31, 89, 100, 102, 104) Positive maternal interactions during feedings while in the ICU are predictive of later mother-baby interactions after discharge. (104) Outcomes are improved when parents are present and participate in their baby’s care. (36, 89, 109, 110)

Standard 5, Feeding: Caregiving activities shall consider baby’s response to input, especially around face/mouth, and aversive non-critical care oral experiences shall be minimized.

Competency 5.1: Suctioning, respiratory support, and other oral care shall be considered as a potential aversive input to the face and mouth, and be performed only as necessary and with conscious attention to minimizing distress.

Evidence-based rationale:

Preterm babies are at high risk of developing sensory aversive responses and feeding disorders. (15, 111-113) Human milk may provide immune benefits when used for mouth and oral care. (69) Babies held skin-to-skin may nuzzle at breast and benefit from the sensory inputs associated with human milk and nuzzling. (23, 86) Providing smells and tastes of human milk may improve the transition to oral feedings. (114) Care shall be taken when mouth care is necessary, to minimize discomfort and aversive experiences as babies show physiologic instability with unfamiliar touch to the face. (2, 44-47)

Standard 6, Feeding: Professional staff shall consider smell and taste experiences that are biologically expected.

Competency 6.1: Odors/tastes of expressed human colostrum and/or milk shall be provided as soon after birth as medically indicated/allowed.

Competency 6.2: Odors/tastes of human milk shall be provided as a way to increase interactions/familiarity with the baby’s m/other.

Competency 6.3: Skin-to-skin care shall be facilitated early and often. (see skin-to-skin standards).

Evidence-based rationale:

Babies are more stable during skin-to-skin holding. (see skin-to-skin standards). They benefit from smells and tastes of human milk. Providing smells may help with earlier transition to breastfeeding. (2, 23, 69, 86, 114)

Standard 7, Feeding: Support of baby’s self-regulation shall be encouraged, especially as it relates to sucking for comfort.

Competency 7.1: Non-nutritive sucking (NNS) opportunities shall be offered to all babies in the ICU, for comfort, during gavage feeds, and as support during painful procedures.

Competency 7.2: Mothers shall be encouraged to be available for the baby’s exploration/comfort at breast.

Evidence-based rationale:

Non-nutritive sucking opportunities shall be encouraged, as they are correlated with improved stability in the baby, better transition to oral feedings, and calming effects during painful procedures. No detrimental effects on breast feeding have been shown related to the use of non-nutritive sucking in the ICU. (63, 64, 90-92, 115-119) Early breast exploration supports the transition to full oral feeding, and does not appear to have detrimental effects. (62-64, 74, 83, 84, 90, 120)

Standard 8, Feeding: Environments shall be supportive of an attuned feeding for both the feeder and the baby.

Competency 8.1: Environments shall be as free of distractions as possible, in order to support both the baby and the feeder to focus on the feeding. Distal environmental influences include ambient noise, lighting, activity around the bed space, availability of a comfortable chair for the feeder, and free from distractions (e.g., phones, conversations). Proximal environmental influences include positioning of the baby in midline with neutral/slight flexion in body/neck as well as postural support for the entire body of the baby.

Competency 8.2: The use of special positioning (e.g., side-lying, upright) shall be individualized based on the baby’s needs, documented, and assessed for change as the baby develops feeding competence.

Competency 8.3: Special bottle nipples/bottle systems should be adjusted based upon the infant’s ability to maintain physiologic stability and develop/use suction appropriately. Flow rates from bottles should be documented and assessed according to the baby’s emerging competence. Bottle/nipple options should be individualized for the baby’s abilities and modified as the baby grows, gets stronger, and changes.

Evidence-based rationale:

Environments are known to influence baby sleep and behaviors, and should be attended to accordingly. (see sleep and arousal standards). (12) Attuned feeding environments are ones in which both the feeder and the baby are able to focus on the feeding as opposed to the environment. (121) An attuned environment supports the m/other’s feeling of belonging as part of the care team. (see pain and stress-families, standard). It also provides privacy and a separation from distractions and other people during the feeding. (121) Feeders who mindfully prepare the environment of the baby’s space prior to the feeding, attending to the lighting, seating, noise, and equipment necessary, support improved feeding skills. (2, 21, 22, 24, 122) Babies who are positioned in midline with slight flexion, with postural support, are better able to coordinate sucking/swallowing and breathing. (24, 123) Specialized positions, such as elevated sidelying or upright to achieve horizontal milk flow, may support organization of the suck/swallow breathe sequence, and may be beneficial while the baby is learning to eat. (20, 24, 124-129) However, babies may not require a specialized position, and babies are often successful at transitioning to a more traditional cradle-hold for bottle feeding once they have established a mature sucking pattern. (125) Bottle flow rates influence the way a baby uses suction, and can influence physiologic stability. (25, 50, 52, 53, 65, 130, 131) Caregivers should be knowledgeable about bottle nipple flow rates as well as infant behaviors that might indicate the need to change the flow rate. (50, 52, 53, 65, 130-135)

Standard 9, Feeding: Feeding management shall focus on establishing safe oral feedings that are comfortable and enjoyable.

Competency 9.1: Feeding shall minimize risks for aspiration and/or other adverse cardio-pulmonary consequences.

Competency 9.2: Modifications to support feeding shall be individualized, documented, verbally shared among professionals and parents to facilitate continuity, and used in the development of a comprehensive feeding plan. Communication shall focus on decreasing variability between feedings and on supporting the baby’s skill development.

Competency 9.3: Babies shall not be forced to suck or finish a prescribed volume orally if they are losing physiologic stability, are no longer actively sucking, or are asleep.

Competency 9.4: If, despite maximal supports, pleasurable feeding experiences cannot be achieved, babies should be held and be provided smells/tastes and an opportunity to engage in non-nutritive sucking while being given their feeding enterally.

Evidence-based rationale:

Feeding efficiency and volume are related to alertness prior to feeding, maturation, and comorbidities. (55, 136) Being held during gavage feedings, and getting smells/tastes during gavage, can improve the baby’s eating skills. (114-116, 120) When babies are offered feedings based upon readiness behaviors, and when the feedings are stopped when baby’s show satiation behaviors, they have fewer adverse events (apnea, bradycardia, desaturation) and transition to feedings more quickly, with similar weight gain. (10-12, 14, 16, 17, 20-22, 25, 26, 42, 54, 67) Feedings should focus initially on establishment of enjoyable experiences where skill attainment is the goal, to avoid aversive experiences. (23, 24, 60, 113, 135) Repeated aversive experiences may place the baby at higher risk for feeding aversions, using a classical conditioning learning paradigm. (137) Repeatedly forcing a baby to finish a feeding or to continue despite losing physiologic stability may lead to aversive experiences and ultimately may increase risk of oral aversions and feeding disorders. (23, 113) These behaviors may also indicate the baby is allowing fluid into the airway. (138) Feeding modifications that are individualized, applied consistently, and support eating skills can improve feeding outcomes. (15, 16, 39, 63, 64, 66, 139, 140) Improved consistency of caregiver actions during feedings improve feeding outcomes and may decrease length of stay. (15, 16, 39, 139, 141, 142)

Standard 10, Feeding: ICUs shall include interprofessional perspectives to provide best feeding management.

Competency 10.1: Intensive care policies and time management shall provide opportunities for professional staff and the baby’s family to discuss feeding management.

Competency 10.2: Interprofessional team members shall review the parental involvement in care, and the baby’s regulation and stability in the context of feeding and weight/gain/energy conservation, during rounds.

Competency 10.3: Feeding plans and the progress of the baby’s feeding skills should be monitored and documented. Changes to the feeding plan shall be made when an infant is not stable or not improving, as documented in the feeding plan. Changes should address improving the comfort and safety, as well as ability to eat appropriate volumes.

Competency 10.4: Interprofessional feeding management shall be driven by information gathered, consistently applied, and regularly updated in the application of the baby’s individualized feeding plan.

Competency 10.5: Interprofessional feeding management shall be driven by the m/other’s expressed desires (to breast feed and/or bottle feed), as well as the baby’s stability and behavioral communication during feedings.

Evidence-based rationale:

Feeding outcomes are improved when feeding plans are developed by interprofessional teams, consistently followed, and monitored for compliance. (2, 15, 39, 139) The development of feeding plans requires time for team members to meet and discuss options, at a time when the family is present. Parents should be able to attend these discussions, and to play a role in deciding what is best for their baby. (see parenting standards). The behaviors of the baby (before, during and after the feeding) shall be documented and shall guide decisions. (10, 14, 20-24, 60, 67, 122, 141) Plans shall be individualized according to the baby’s current needs. (64, 140) The safety and skill of the baby (learning to coordinate sucking/swallowing and breathing) shall be paramount to other considerations. Baby instability during/after feedings shall be considered as relevant information that shall prompt a re-evaluation of the plan. Efficiency, endurance, and volume are all measurable outcomes. (24)

Standard 11, Feeding: Feeding management shall consider short and long-term growth and feeding outcomes.

Competency 11.1: Feeding shall be seen as a neurodevelopmental progression, with the ICU building a foundation for further learning/development around eating.

Competency 11.2: Professional services shall be made available to families to ensure optimal nutrition after discharge whether breast, bottle, tube feeding, or a combination of those feeding approaches.

Competency 11.3: Post-discharge, feeding outcomes shall be monitored to inform care, document outcomes and assess potential changes in feeding approaches.

Evidence-based rationale:

Feeding is influenced by medical factors, maturation, and experience. (15, 39, 58, 59, 136, 139) Medical comorbidities are highly correlated with delayed acquisition of oral feedings, and long-term feeding disorders. (143-146) Feeding skills change over time, and are considered part of a neurodevelopmental process. (48) Preterm babies lag behind their full-term counterparts in skill acquisition. Mothers may struggle with understanding their baby’s behaviors and benefit from ongoing support after discharge. (32, 33) Preterm babies lag behind their full-term counterparts in skill acquisition. (9, 102, 147-149) Preterm babies have an increased risk of long-term feeding disorders compared to term babies. (113, 150-153) Late preterm babies have similar feeding problems in the first year as early born preterm babies, and require similar support after discharge. (154) Feeding support while in the ICU, as well as after discharge, is a standard of care in the U.S. and other countries. (2, 140, 155)

*Acknowledgement of Diane Maroney for consenting to our use of the concept of “imagine…” statements written by parents/families who have experienced intensive care; and to our parents for their thoughts.