IFCDC- Recommendations for Best Practice to Support Sleep and Arousal

“Imagine…one day being able to rock my twin sons to sleep without tubes and equipment.”*

These committee members had primary responsibility for this section:

Rosemarie Bigsby, ScD, OTR/L, BCP, FAOTA

Amy Salisbury, PhD, APRN-BC

Questions to consider when starting your process Sleep And Arousal Interventions For The Newborn

Check sheet to assess this area before and after intervention.

Successful change only happens in relation to the system. To review systems concepts check this section.

Standard 1, Sleep and Arousal: Intensive care units (ICUs) shall promote developmentally appropriate sleep and arousal states and sleep wake cycles.

Competency 1.1: The ICU policies and procedures shall promote periods of time for babies’ undisturbed sleep.

Competency 1.2: The ICU policies and procedures shall support stable states of arousal to optimize interaction, assessment and feeding.

Competency 1.3: The ICU shall implement a system for documentation of the individual baby’s sleep and arousal states and cycles.

Competency: 1.4: States of arousal and sleep shall be documented as they are an integral part of routine assessment of vital signs and physical condition of the newborn. Assessment shall a) identify behavioral patterns indicative of and duration of periods of arousal and sleep, and b) form a basis for recommendations to enhance behavioral organization and energy conservation.

Competency 1.5: Assessment and documentation of arousal and sleep shall occur: a) at rest, prior to caregiving, b) during care/handling (including holding), c) prior to and during feeding, d) immediately following care, and shall include position of infant and location (e.g., prone-nested in incubator vs. prone, skin-to-skin on mother’s chest).

Competency 1.6: Presence and description of participation of family & visitors, sound level and lighting level should be documented to provide a context for state organization.

Competency 1.7: Family members in the ICU shall be provided education regarding the potential benefits of assessment of states of arousal and sleep to inform the baby’s plan of care.

Competency 1.8: Regularly scheduled interprofessional education to ensure competence in assessing infant arousal and sleep states shall be developed, implemented and evaluated.

Competency 1.9: Interprofessional education shall include evaluation of the professional’s ability to assess infant positioning, arousal, sleep, and readiness for and quality of participation in breast and bottle feeding, and interaction.

Evidence-based rationale:

Both quantity and quality of sleep are essential to normal growth and development of preterm and term babies. (1) Following a period of near continuous movement during the early fetal period, cyclical rest-activity patterns begin to develop - after the first trimester. (2, 3) These patterns represent the emergence of organized active and quiet sleep periods that are precursors of Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and non-REM sleep states, respectively; and awake states. (4, 5) The vast majority of late fetal gestation is spent in sleep states relative to wake states. Wake periods gradually lengthen, from brief periods at term age to longer, more organized periods with a circadian rhythmicity emerging over the first 6 post-natal months. (6) These predictable age-related patterns of sleep and arousal can be observed from the preterm to term gestational ages, (7, 8) throughout infancy, (9-13) and into adulthood. (14) These developmental changes reflect maturation and change in the central nervous system (CNS) as well as coordination with the peripheral nervous system. Sleep, in turn, may facilitate CNS plasticity through enhanced production of the structures involved in building neuronal circuitry. (15, 16)

Sleep-state organization is the ability to transition smoothly between states of sleep and wakefulness, and to regulate the transition between states of alertness. These capabilities reflect developmental maturation, including predictable cortical and subcortical brain activation patterns. (6, 17) Sleep state cycling between REM and non-REM (NREM) sleep has been documented by EEG as early as 25 weeks gestational age, (8) with a widely varying cycle length, most commonly ranging from 30 to 100 minutes. Active sleep is predominantly observed at earlier gestations, with increasing durations of quiet sleep with maturation. Regulation of arousal, from sleep to wakeful states, reflects not only neurological maturation, but the integrity of the nervous system. There are characteristic patterns of sleep and arousal that can be specifically associated with medical conditions such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, congenital heart disease, neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), errors of metabolism, and chronic lung disease. (18, 19) Moreover, low arousal at term age is a risk factor for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). (12)

Sleep and arousal states are tied to physiologic functions, such as body temperature, (20) breathing, heart-rate, (21) and digestion, including gastro-esophageal reflux events, which occur more frequently during awake states. (22) Persistence of sleep-disordered breathing has been demonstrated among preterm babies born at <32 weeks, with associated lower IQ, memory and visual-spatial performance at school-age, compared to term-born peers. (23) The characteristics of sleep states may also predict later outcomes. Preterm babies with a REM sleep in which rapid eye movements are minimal were at increased risk of developmental delay at 6 months corrected age. (24)

Regulation of states of arousal has the potential to impact participation in feeding (25) and social interaction, and has been shown to predict neurobehavioral development later in infancy, at school age, and in adolescence. (24, 26, 27) Organized sleep can be considered a clinical marker and facilitator of normal neuro-development. (28, 29) With all of these benefits, sleep should not be unnecessarily externally disrupted.

The importance of sleep for energy conservation, growth and healing of babies in the ICU is widely acknowledged, and support of babies’ sleep is typically included in recommendations for developmentally supportive care. Sleep state and level of arousal during routine care may influence baby’s responses to care and readiness for feeding. For example, preterm babies desaturated more frequently when handled during active sleep compared to handling in quiet sleep or wake states. (30) Handling techniques and positioning also have a significant influence on sleep and wake states. (16, 31) However, ICU staff do not necessarily come prepared with knowledge of how to assess arousal, sleep, and positioning. (32, 33)

ICU staff need to be specifically educated to the benefits of assessing the baby’s sleep and arousal state before, during and after care and handling, and the importance of incorporating interventions that may reduce unnecessary stress. Guidelines for valid criteria for determining states of arousal in preterm and term infants have been established for both direct observation and physiologic methodologies. A combination of observed behaviors (rapid eye movements, facial movements, gross body movements) and physiologic parameters (respiration and/or heart rate variability) provide a structured approach for determining states of sleep and arousal which can be incorporated into routine assessment by ICU staff. (6, 11, 34-39)

Cultural buy-in among ICU staff occurs more readily when training and evaluation experiences incorporate peer participation, and when care practices are included in routine documentation according to a defined standard of care. (32) A contextual approach, incorporating documentation of routine observations of the baby’s states of arousal before, during and after care, presence and level of participation of family members in care, and features of the environment has the potential to inform the team regarding the baby’s ability to tolerate/ participate in developmentally appropriate activities of daily living such as routine handling during care, feeding, being held and obtaining adequate sleep.

Documentation enhances compliance with a higher standard of care and provides objective data to inform decisions made by the ICU medical team, as well as family members, to optimize the plan of care. This documentation, as part of the electronic medical record, also provides data for quality improvement measures. (40, 41)

Standard 2, Sleep and Arousal: The ICU shall provide modifications to the physical environment and to caregiving routines that are specifically focused on optimization of sleep and arousal of ICU babies.

Competency 2.1: The ICU shall make provisions for space and furnishings that optimize babies’ sleep and family participation in sleep protection and interaction during arousal.

Competency 2.2: The ICU shall provide optimal environmental conditions to support sleep, to achieve comfort and behavioral regulation during care and to enhance baby-caregiver interaction through: a) reduction of sound levels, b) provision of natural lighting, c) adjustment of lighting and diurnal cycling of lighting, d) adjustment of temperature, and e) provision of positioning aids.

Evidence-based rationale:

Regulation of sleep and arousal are essential human functions that are easily impacted by ICU environment including caregiver presence at bedside, sound levels, lighting, and temperature. (30, 42-49) Sound level changes as small as 5-10 dB can increase awakenings by a factor of three. (46) Early exposure to cycled light shows a benefit to sleep maturation and weight gain in most studies. (50-52) For babies not receiving hypothermic treatment, warm temperatures that facilitate distal vasodilation, are linked to rapid and organized sleep onset. (20) Conformational positioning may improve sleep in preterm babies, (39) particularly in the flexed, tucked posture. (53)

Private environments have been found to have more prolonged periods of silence, although noise variance can be as high as in the open bay. (54) Care should be taken to provide speech exposure for those babies whose parents cannot be present, to support language and cognitive development. (55, 56) Pod or open bay units may be made quieter by modifications in materials and by staff training. (57)

Standard 3, Sleep and Arousal: The ICU shall encourage family presence at the baby’s bedside and family participation in the care of their baby.

Competency: 3.1: Policies and procedures in support of parent participation in routine care and sleep-promoting skin to skin holding shall be developed, implemented, monitored, and routinely evaluated.

Competency 3.2: Uninterrupted and extended time for the baby to sleep during parental skin-to-skin care shall be promoted as early in the baby’s hospital stay as possible.

Competency 3.3: Education regarding benefits of sleep during skin-to-skin care will be provided to both parents and professionals.

Competency 3.4: Education for parents shall be provided regarding the importance of facilitating adequate arousal and sleep for energy conservation and optimal feeding, including assessment of arousal states for breastfeeding and/or bottle feeding, and for interaction.

Evidence-based rationale:

Parent participation in care, such as face care, mouth care, non-nutritive sucking on a pacifier, diapering, positioning, soothing, facilitated tucking during uncomfortable procedures, and swaddled bathing may positively impact infant regulation of states of arousal. (31, 58, 59) Skin-to-skin holding provides neutral body warmth, muffled body sounds, and rhythmic chest movements, which contribute to improved sleep quality in the preterm baby. Deep sleep and quiet alert/awake states are increased during this intervention, while light sleep, drowsiness and active alertness are decreased. (60-63)

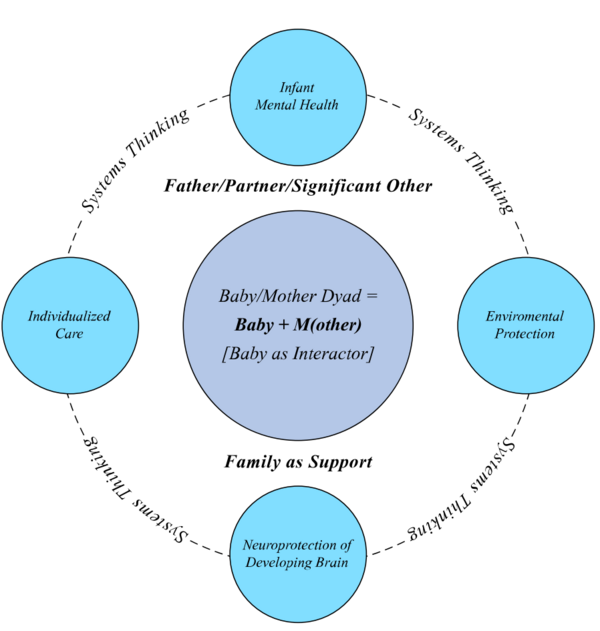

A systems model for intervention that emphasizes: a) the appropriateness of the sensory experience and of its timing, to the developmental stage of the infant, and b) the potential for regulatory and buffering effects of caregiving, holds promise in guiding further interventions aimed at enhancing regulation of states of arousal and sleep, and improving parent-infant interaction and emotional regulation. (61, 64-66) Parent sensitivity training and parent participation in routine care have a demonstrated impact on reducing parental anxiety, as well as increased infant brain volume and growth by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), (67) improved infant-parent interaction at 4 months of age, and infant neurodevelopment and social relatedness at 18 months. (68, 69)

Standard 4, Sleep and Arousal: Interprofessional team members shall review trends in documented arousal and sleep as part of routine data presented on rounds, within the context of feeding and weight gain/energy conservation and parent involvement in care.

Competency 4.1: Consultation by a qualified ICU therapist/developmental specialist should be obtained to assess baby’s behavioral/developmental strengths and needs when the baby is considered at risk for developmental sequelae and/or the family would benefit from guidance.

Competence 4.2: Collaboration between professionals and the baby’s family to determine appropriate modifications to the care/sleep/feeding routines shall be accommodated, documented and evaluated.

Competence 4.3: Ongoing anticipatory guidance and support of baby’s state and circadian rhythm development and social interaction with m(other) and family members shall be provided both in the ICU and as the family transitions to home services.

Competence 4.4: Consultation among therapists/developmental specialists, nursing and medical staff and parents/family members should be scheduled at a convenient time to optimize collaboration in assessment and planning for sleep protection and social/caregiving interactions.

Evidence-based rationale:

Infants and families receiving developmental support through Newborn Individualized Developmental Care Assessment Program (NIDCAP) services within 6 days of admission, had shorter lengths of stay by an average of 25 days, compared with later initiation of developmentally supportive care. (70) These findings suggest that early initiation of parent-staff collaboration in support of regulation of states of arousal and development, may contribute to discharge at earlier postmenstrual ages.

Preterm infants whose parents provide skin-to-skin holding have longer periods of deep sleep and quiet awake states compared with control infants. (60, 61) Moreover, when parents of preterm infants receive anticipatory guidance in providing developmental support through their ICU stay (e.g., sensitivity to states of arousal and to behavioral communication during routine care and skin-to-skin holding), their infants show improved brain maturation on MRI, compared with controls. (61, 67) Parents participating in developmentally supportive care report that they value these practices, and yet, they report inconsistencies between staff in being “on board” with this approach to care as one of the most significant challenges to performing their parental role. Ongoing practical education and guidance in supporting parental role, without judgment, is essential to a positive outcome. (71)

Standard 5, Sleep and Arousal: Families shall be provided multiple opportunities to observe and interpret their baby’s states of arousal and sleep, and to practice safe sleep positioning, to support successful parent-infant participation in care routines during the transition home.

Competency 5.1: Education shall be provided to the family throughout the ICU stay to enhance their recognition of their baby’s states of arousal and their confidence and competence in supporting regulation during routine care.

Competency 5.2: Family education shall include the expected developmental trajectory of their baby’s sleep and awake states, including the expectation that positioning and strategies for supporting regulation of arousal and sleep will change over time.

Competency 5.3: AAP Safe Sleep Recommendations {Moon, 2016 #940} shall be explained and modeled for families in the ICU for a period prior to discharge.

Competency 5.4: Families shall be educated to the value of daily routines, including regular intervals of awake and sleep time in their baby’s day. Education should include soothing strategies and suggestions for promoting positive sleep associations to optimize rest as well as age-appropriate periods of interaction and play.

Evidence-based Rationale:

Positioning strategies used during a prolonged ICU stay are not recommended for home-use, according to AAP Safe Sleep Recommendations (72) therefore families need specific guidance in providing a safe sleep environment as they prepare for the transition home. (73-75) Family education regarding the expected trajectory of sleep/wake cycles for developing babies (6, 76, 77) needs to begin early in their ICU stay, to allow for modeling of safe sleep practices prior to discharge (78-80), and appropriate provision of sleep-wake routines in early infancy (81, 82).

*Acknowledgement of Diane Maroney for consenting to our use of the concept of “imagine…” statements written by parents/families who have experienced intensive care; and to our parents for their thoughts.